Bombino

ARTIST BIO:

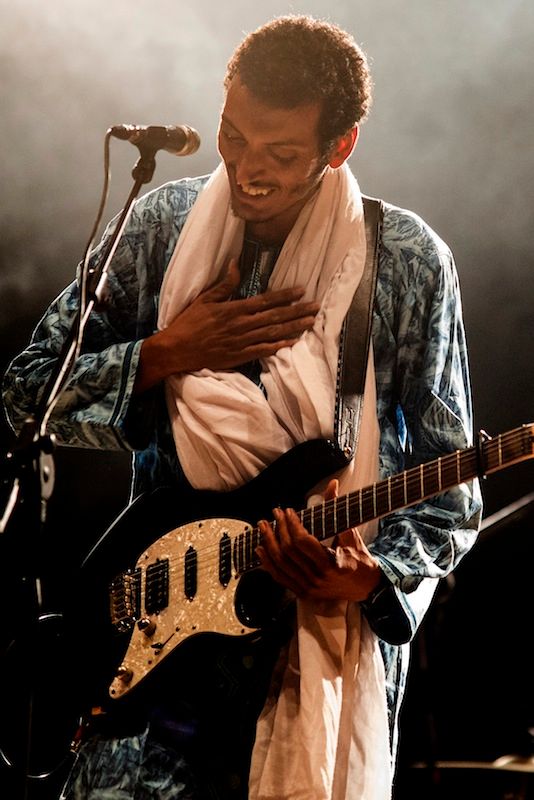

"The Sultan of Shred" - New York Times

"The World's Greatest Guitarist" - Noisey

"A groove you can ride to the end of the earth" - Billboard

"Fluid and bluesy, his guitar playing is more than just an agile dance between rhythm and melody. It speaks and breathes across centuries." - NPR

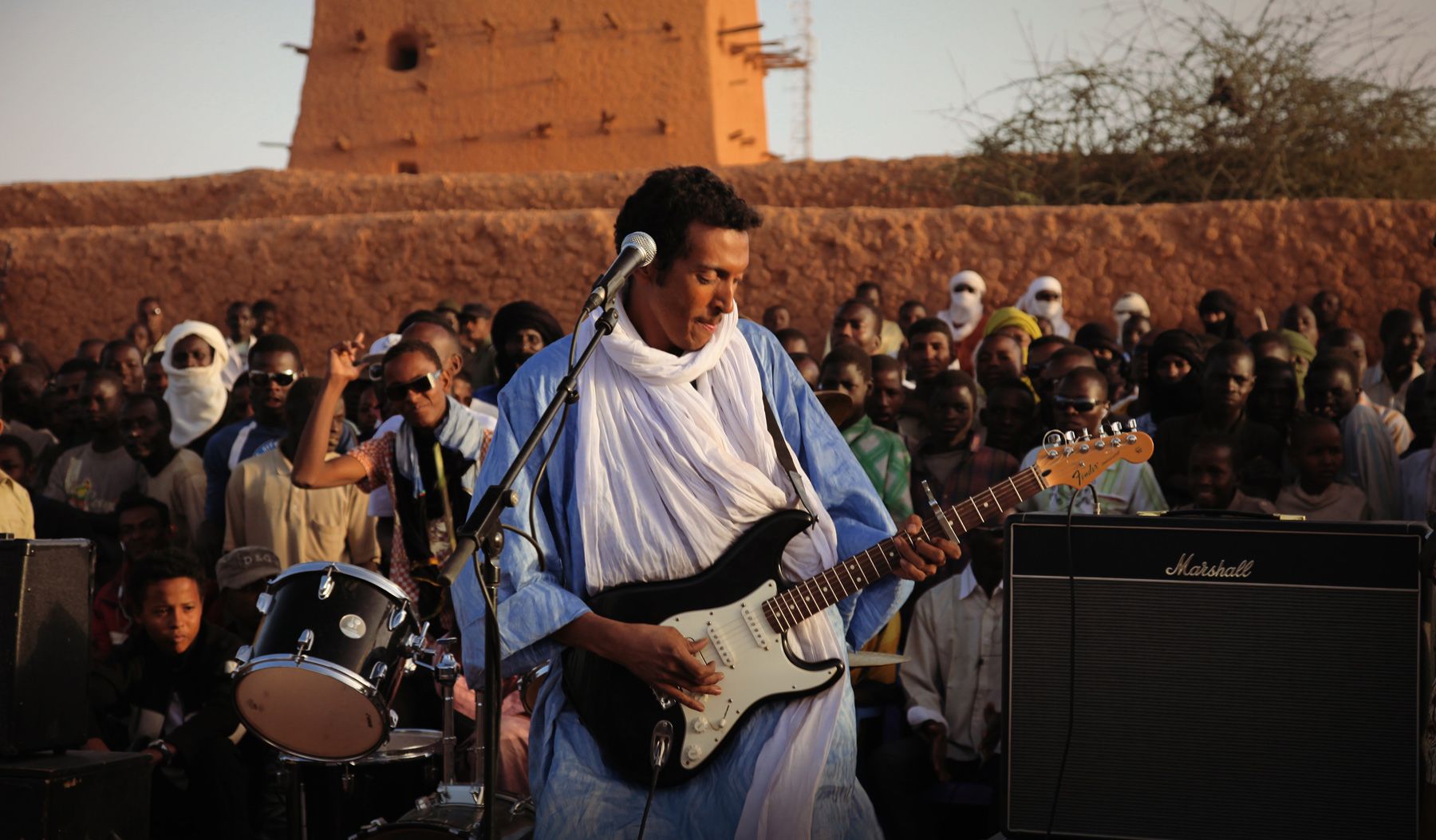

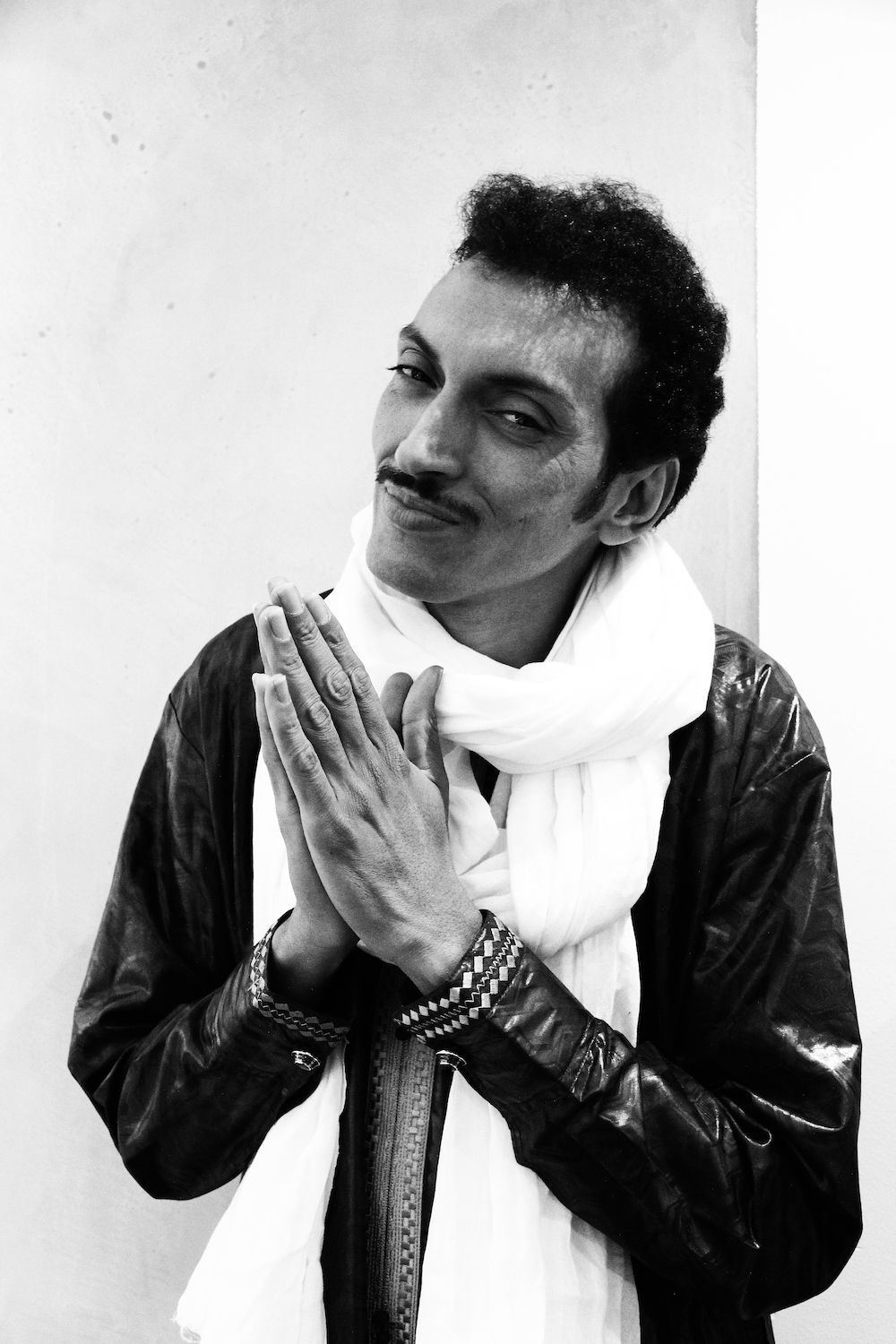

Guitar luminary + Tuareg folk hero Omara “Bombino” Moctar knows the nomadic life well. Being constantly on the road for his music while also perpetually on the move throughout the Sahel region of Africa is the norm. So when the pandemic brought the world to a screeching halt, Bombino found himself in an unfamiliar space: being in one place. “I’m used to traveling virtually every week and then I was locked down for two years,” he says from his home in Niamey, the capital of Niger. “On the positive side, I get back in touch with my home and spend real time there with my family for the first time in a long time.”

What resulted was the follow-up to 2018’s Deran, a record that turned Bombino into the first-ever Grammy-nominated artist from Niger. This new collection of songs, entitled Sahel after the African region spanning East-West from the Atlantic Ocean to the Red Sea, is Bombino’s most personal, powerful, and politically-minded work to date. It’s also his most sonically diverse, a quality he set out to achieve from the start, and one that is meant to directly mirror the complex tapestry of cultures and people that make up the Sahel region itself. He says, “the general plight of the Tuaeg is always on my mind and while I’ve addressed it in my music all along, I wanted to give it a special focus on this album.”

To bring the songs to life, Bombino worked closely with Welsh producer/ mixer David Wrench (David Byrne, Frank Ocean, Caribou, Goldfrapp, Erasure, The xx, Sampha), decamping with his bandmates to a studio in Casablanca for ten days to lay down the album. “Bombino’s an incredible musician, easily one of the best musicians I ever worked with,” Wrench says with fondness of seeing the Tuareg guitarist up close. “What he does looks effortless, but it's so complex. It’s such a refined style, it’s so him, it’s unique. It contains all this history in it, it’s amazing.” The feeling is mutual. While Bombino has been fortunate to have sympathetic guitarists like Dan Auerbach and David Longstreth sit in the producer’s chair in the past, Wrench provided a new level of expertise.

“What I love about working with David is just how incredibly fine-tuned his ear is, how incredibly focused he gets in the studio,” Bombino says. “Nothing escapes him. Even the tiniest little things would grab his attention and he would put great focus into the smallest details of the sound.” Time and time again, Wrench would watch Bombino blaze through an amazing take in the studio, then go right back “and double-track it and it’s just perfect. He’s operating on some different level somewhere.”

The ten songs that comprise Sahel range in theme from the plight of the Tuareg to the ache of lost love to the follies of youth. Opener “Tazidert” preaches patience even as the music itself urges you to stand up and move. The driving “Aitma” features Bombino’s sparks-spraying guitar pyrotechnics, punctuated by howling ululations. It’s a call-to-arms delivered in his native Tamasheq. “Let's defend our people because we are the same regardless of our geographical position,” he says as he shouts out the Tuareg throughout the region. He explains: “When you look at the situations in each of the five countries that make up the Sahel (Libya, Algeria, Mauritania, Mali, and parts of Burkina Faso), the Tuareg people are not represented in these governments.” And only recently did that situation change in Niger.

Sahel looks forward and to the past, a mix of new and old songs, but each one of them resonated with Bombino for one reason or another. “A lot of bands go into the studio with a set of tracks that they’ve rehearsed, but that’s not how Bombino works,” Wrench says. “He goes with what he’s feeling at the time and it’s a much more instinctive way of recording. He’s drawing from this memory of these hundreds of songs he’s written. He pulls from that well of his own work and the history of his culture; he pulls out of that what he feels is right.”

“Si Chilan” (Two Days) is one of the oldest songs in Bombino’s extensive repertoire, first written in the 1980s. “I like to put a spotlight on songs that have persisted in my repertoire for a really long time, but haven’t made their way onto an album,” he says. “When you’ve lived with a song for that long, you’re always finding new things in it, new ways to express it. They’re dynamic in that sense – the song will continue to evolve, at least in how I relate to it and perform it. I liken it to honey, a good old song is like honey, it just gets better and better with age.”

Similarly, “Nik Sant Awanha” (My Brothers I Know our Situation) dates to the late ‘90s and is one of Bombino’s most incisive political commentaries to date, lamenting the divisions amid the Tuareg people, the risks of exile, and an even greater existential threat, the loss of Tuareg culture. “Even though geographically the Sahara desert is our home, so many of the Tuareg people are denied or deprived of certain basic necessities throughout the region,” he says. “This has been motivating me a lot, the types of songs I sing and why. I want to get people thinking about the Tuareg, to represent those people who haven’t been represented. They really need a voice.”

Aside from loss of representation in these countries’ governments and the absence of the Tuareg in mainstream culture, Bombino sees that even with the instant interconnectedness that smartphones can bring, “the biggest threat I see is technology and modernization. A small, marginalized culture like the Tuareg risks getting lost in the homogenization of culture.”

For the broader topics that Bombino addresses throughout the album, the hushed acoustic closer “Mes Amis” sings of youth and unrequited love. “It’s important to reflect the personal themes, to connect with people on a personal level, giving them stories and themes they can relate to,” Bombino says, adding that the extra time he spent at home, being with his children, helped to clarify his purpose. “Everything I do is in service to my family, to give to them and to better their situation.”

Wrench’s role was to present Bombino and his band in a way that captured the Tuareg sound (which spans centuries) while connecting it to our immediate present. It’s not a museum artifact, but a living ‘now.’ While Wrench made his name mixing and recording psychedelic rock and electronic music, he heard Bombino as part of that spectrum. “To me, I see him not that far outside of those realms. The rhythms are all in 3s instead of 4s, but it has a similar effect: the repetition and intensity and the feeling it has, it’s not a million miles away from techno. Listening to his music has a similar effect on you: it can definitely take you somewhere quite different.”

With Bombino as your guide, let Sahel take you there as well.